How Do I File My Antitrust Complaint in the European Union? An Example from the Intel Case

Author: Luis Blanquez

As a US company doing business internationally, you might wonder what are the legal rules and procedures currently in place in the European Union to file an antitrust complaint.

First, you should understand that The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) is based on the existence of a single market with free movement of goods and services throughout the European Union. The antitrust rules included in the TFEU, such as those against anti-competitive agreements, abuses of dominant position, certain problematic mergers and state aid, are essential to achieve that free movement.

Second, an important distinction from US antitrust law is that EU antitrust law is mainly enforced by public authorities: by the European Commission at EU level, and by national competition authorities (NCAs) at national level.

Third, EU antitrust law is also enforced—to a lesser extent—through ordinary litigation before the appropriate national courts of each Member State.

Last but not least, we shouldn’t forget that each Member State within the EU has also its own domestic antitrust rules, often mirroring EU rules, but sometimes with important procedural and substantive differences.

How the different antitrust laws are applied in the EU between NCAs, the European Commission and national courts, deserves an independent post on its own. For now, however, just keep in mind that as a plaintiff, you could also file an antitrust complaint in the EU before a national court.

In the meantime, if you want to know more about this issue, please see: (i) Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 on the implementation of the rules on competition, (ii) Commission Notice on the co-operation between the Commission and the courts of the EU Member States in the application of Articles 81 and 82 EC (See more information here), and (iii) Notice on Cooperation within the network of competition authorities in the European Competition Network (See more informationhere).

Let’s return to our discussion on the application of EU antitrust rules by the European Commission. In the European Union, the Directorate General for Competition of the European Commission (“the Commission”), together with NCAs, directly enforces EU competition rules, Articles 101-109 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. The two most important articles, for the purpose of this post, are articles 101 and 102 TFEU.

Article 101 of the Treaty prohibits agreements between two or more independent market operators that restrict competition. It covers: (i) horizontal agreements between actual or potential competitors operating at the same level of the supply chain; (ii) and vertical agreements, between firms operating at different levels, such as an agreement between a manufacturer and its distributor.

Article 102 of the Treaty prohibits dominant firms from abusing that position, for example, by charging unfair prices, by limiting production, or by refusing to innovate to the prejudice of consumers.

HOW DOES AN ANTITRUST CASE START IN THE EU?

- The investigation

For Article 101 TFEU cases, the Commission and NCAs have important investigative powers under Regulation 1/2003.

The initiation of a Commission investigation might be the result of: (i) the Commission (or an NCA) launching an inquiry of its own initiative; (ii) a third party with information who approaches the Commission, such as a competitor or customer, (iii) a party to a cartel (or anti-competitive agreement) acting as a whistleblower under the existing leniency program, or (iv) when an NCA refers a case with a cross border element to the Commission through the ECN network.

Under Article 102, a case can originate either upon receipt of a complaint or through the opening of an investigation at the commission’s initiative.

Once the Commission decides to investigate a case, it will start collecting further information, either through its formal powers of investigation under Article 18 of Regulation 1/2003 (the so called “Requests of Information”), or through an unannounced inspection or “dawn raid”.

The Commission can conduct a dawn raid under an “authorization” or under a “formal decision”. A firm may refuse to submit to an inspection for an authorization. Such refusal, however, might result in future fines and the adoption of a formal decision by the Commission, this time imposing a duty to co-operate on the firm.

During a dawn raid, the Commission may, among other things: (i) enter the premises of the company being inspected, (ii) examine the records related to the business, (iii) take copies of those records, (iv) seal the business premises and records during an inspection (and if broken, impose fines), and (v) ask staff members or company representatives questions about the subject matter and purpose of the inspection and record the answers. Commission officials are usually assisted by officials from the relevant national competition authorities.

- The statement of objections (“SO”), Article 7 prohibition decisions and Article 9 settlement decisions

If the Commission’s investigation confirms the competition concerns, the regulator will prepare and address a written statement of objections (SO) to the parties. At this point, the parties have certain defenses: First, they are entitled to have access to the file, so they can see all non-confidential documents from the Commission’s investigation. Second, the parties are entitled to respond to the SO, both in writing and at an oral hearing., The oral hearing is conducted by an independent Hearing Officer.

The Commission may then: (i) abandon its investigation and close the case if there is insufficient evidence, (ii); adopt a commitment decision under Article 9 of Regulation 1/2003, by which the Commission does not have to conclude on the existence of an infringement of the antitrust rules, imposing no fines; or (iii) draft a prohibition decision under Article 7 of Regulation 1/2003, which is submitted first to the Advisory Committee composed of representatives of the Member States’ competition authorities, and finally to the College of Commissioners, which adopts the decision.

A company that has infringed EU antitrust laws (prong (iii) above) is subject to fines. The fines imposed by the Commission reflect the gravity and duration of the infringement. They are calculated under the framework of the 2006 Guidelines. If you want to know more about how the Commission calculates antitrust fines, please see here.

- Judicial review: Right of appeal

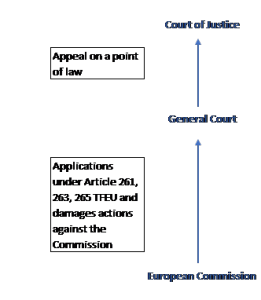

The addressees of a Commission decision have the right to appeal to the EU General Court in Luxembourg.

First, in the context of unlimited jurisdiction for matters of fact and law, under Article 261 TFEU and Article 31 of Regulation 1/2003, the General Court has the power to assess the amount of fines imposed by the Commission.

Second, under Article 263 TFUE, the General Court may review the legality of those decisions limited to four grounds of annulment: (i) lack of competence, (ii) infringement of an essential procedural requirement, (iii) infringement of the TFEU or of any rule of law related to its application, and (iv) misuse of powers.

As a final step in the judicial review process, companies can appeal judgments of the General Court to the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU). But these appeals to the ECJ are limited to questions of law only:

A RECENT EXAMPLE: THE INTEL CASE JUDGMENT ON ABUSE OF A DOMINANT POSITION

On May 2009, the Commission fined Intel, a US microchip manufacturer, with €1.06 billion for abuse of its dominant position in the market for central processing units (“CPUs”).

The Commission concluded that Intel (i) granted unlawful exclusivity rebates to four computer manufacturers: Dell, HP, NEC and Lenovo on the condition they would purchase all (or almost all) of their CPUs from Intel, and (ii) made payments to retailer Media Saturn Holding, also on the condition it would only sell computers containing Intel’s CPUs. In all cases, the rebates were conditioned on exclusivity or quasi-exclusivity, either for all customer purchases, or for certain types of products.

As a general comment, exclusivity, fidelity or loyalty rebates are those conditional upon a purchaser buying all (or almost all) the products it needs from a dominant supplier. According to previous EU case law, such rebates have been characterized by their very nature as abusive, regardless of the circumstances around them, or whether they are capable to restrict competition and foreclose competitors from the market. By contrast, quantity rebates, exclusively linked to the volume of purchases from the producer concerned, are presumed to be valid and not abusive.

[You can read our article on exclusive dealing agreements under US antitrust law here.]

Intel challenged the Commission’s decision, arguing that not all exclusivity rebates provided by dominant undertakings must be prohibited. Instead, Intel’s argument suggests the Commission to analyze them on a case-by-case basis to determine whether they restrict competition and foreclose competitors in the market that are just as efficient.

On June 2014, the General Court dismissed Intel’s appeal, upholding the Commission’s legal characterization of the abusive conduct. The General Court stated that Intel’s exclusivity rebates were unlawful by their very nature, and there was no need for the Commission to examine all relevant circumstances.

On September 2017, the CJEU set aside the General Court’s judgment, and referred the case back to the General Court. The CJEU ruled that exclusive or quasi-exclusive arrangements may be deemed lawful if the dominant company can demonstrate that (1) such agreements are not capable of foreclosing competitors that are as efficient as the dominant company, or (2) the foreclosure effect is outweighed by objective justifications.

In a nutshell, the most relevant points of the judgment are:

- Regardless of the circumstances of the case, under EU law, a dominant company has a special responsibility not to distort genuine competition, and there is a presumption of illegality when a dominant company enters into exclusivity agreements. Therefore, an obligation or promise from a customer to obtain all, or most of their requirements exclusively from that undertaking, is prima facie abusive, and contrary to Article 102 TFEU.

- But the court further states that if the undertaking argues—on the basis of supporting evidence—that its conduct was not capable of restricting competition, the Commission must analyze the capacity of the rebate to foreclose as efficient competitors from the market.

- To this end, the Court provides a non-exhaustive list of elements that the Commission is required to analyze: (i) the extent of the undertaking’s dominant position on the relevant market, (ii) the share of the market covered by the challenged practice, (iii) the conditions and arrangements for granting the rebates, including duration and amount, and (iv) the possible existence of a strategy aiming to exclude competitors that are at least as efficient as the dominant undertaking from the market.

- The analysis of the capacity to foreclose is also relevant in assessing prong (2) above: whether a system of rebates which, in principle, might fall within the scope of the prohibition laid down in Article 102 TFEU, is nevertheless objectively justified.

- The Court also confirmed the relevance of the application of the “as efficient competitor test” or “AEC Test” included in the Commission’s Article 102 Guidance Paper to assess the capacity of rebate cases, based on exclusive or quasi exclusive arrangements, to foreclose as efficient competitors and restrict competition. The AEC test focuses on whether the dominant company’s conduct is likely to prevent competitors that are as efficient as the dominant undertaking from expanding or entering the relevant market. The Court had previously applied the test in anticompetitive pricing cases by dominant undertakings, such as Deutsche Telekom, TeliaSonera and Danmark I. Now it also confirms its application in the context of rebates with a foreclosure effect.